Voices from Oaxaca: "I will keep fighting until my husband is released"

Yolanda Barranco Hernández will never forget the morning of 18 May 2013. It started with a loud noise. Seven men carrying heavy weapons broke down the door of her house. They were looking for her husband, Damián Gallardo Martínez. They didn't present any warrant. They said they were there to arrest him and they took him away.

For 30 hours, Damián was held incommunicado. He was tortured and forced to sign a false confession saying that, together with his colleagues from Sección 22 del Sindicato Nacional de Trabajadores de la Educación – SNTE (22nd Section of the National Union of Education Workers), he was involved in criminal activities. A few days later, Mexican authorities issued a detention order against Damián on fabricated charges of organised crime and kidnapping of minors.

Damian has been in jail since then. He has been ill-treated, tortured and placed in solitary confinement. More than three years after her home was invaded, Yolanda is still seeking justice.

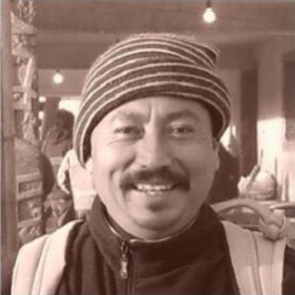

Her husband, Damián, is a Mexican teacher and human rights defender who defended the rights of indigenous communities in the Mixe and Zapoteca regions. In 2006, following the violent repression of a teachers' strike, he became a member of the Asamblea Popular de los Pueblos de Oaxaca – APPO (Popular Assembly of the Towns of Oaxaca). Yolanda is also a teacher and human rights defender.

“For the past three years, I have been advocating for my husband's release, protesting against his arbitrary detention, and against the detention of other activists,” says Yolanda. “But my struggle started even before his arrest: for 30 years we have been fighting to have free education in the state of Oaxaca: we want better schools, better programs, better work conditions”.

In 2013, the Mexican parliament approved a controversial reform of the public school system, without consulting local teachers. Thousands of people, especially in the southern states of Oaxaca, Chiapas, Guerrero and Michoacán, took to the streets to protest and organised long-term strikes and blockades. The reform has been strongly opposed because it will partially privatize public schools, giving further power to private corporations. It doesn't include any reference to indigenous languages and culture in the curriculum, and it introduces standard evaluation tests for the teachers without taking into account cultural and geographic differences.

“The authorities brutally repressed the demonstrations,” explains Yolanda. “In 2015 the negotiations with the government completely fell apart and since then we have suffered threats, intimidation, judicial harassment, physical attacks, arrests, and endless repression. Our work should be in the classrooms, but we have to continue our struggle in the streets”.

Human rights defenders advocating for education rights in the state of Oaxaca have recently reported experiencing intimidation. On the night of 14 July, HRDs Adriana Linares Arroyo and Rubí Cortés Salazar were photographed as they got into their car and were then followed by another vehicle as they drove from Oaxaca to Tlaxiaco. The two human rights defenders have also been the target of anonymous phone calls, acts of defamation, surveillance, and intimidation from individuals who appeared to be connected to police and the military.

The repression against the striking teachers has become increasingly violent and lethal. On 19 June, a police operation against demonstrators in several cities left 11 people dead and over 120 injured. Yolanda's voice still shakes when she recalls the details of that day: “Since the morning, we realised the police were more aggressive than usual. They didn't give us any warrant before attacking the blockade, they immediately started using tear gas. They violated our right to democractically demand change”.

It is not only physical attacks against the human rights defenders. According to Yolanda, the daily abuse is extremely difficult to endure: “Indigenous women are the most targeted. People say we should stay home, they call us indias (indigenous) with a derogatory tone. They insult us with the most horrible expressions, that I cannot repeat. They say that if we are in the streets, it's because we don't have better things to do or because we are looking for men. For us women, the struggle is even harder, but we work together and we know there is always support”.

Yolanda has been working closely with the wives and the families of the other teachers and human rights defenders who have been detained. To date, there are 75 leaders of the teachers' movement in prison.

In November 2014, the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention issued an opinion recognising the detention of Damián Gallardo Martínez as arbitrary, and called for his immediate and unconditional release. Despite the pressure of the UN and international community, Mexican authorities have not discussed his release.

“We have to keep fighting to release my husband and the other prisoners,” says Yolanda. “Because they took away their freedom, and their children are left without a father. We have to keep fighting so that the sacrifice of all the colleagues who were killed, all the blood that was shed, all the people who disappeared, would not be wasted. We know well that our struggle is not going to end in one day. We are struggling against the government and against private corporations and this is hard, but our struggle is a legitimate one, and we have to win it”.